Confident protein datasets for liquid-liquid phase separation studies

Proteins

Tutorial

This website offers an intuitive interface for easily navigating and

retrieving relevant information from the LLPS proteins datasets.

The interface provides comprehensive information on LLPS proteins,

including category specificity,

disorder analysis, category

intersections, and the corresponding database

sources. Users can efficiently filter and explore these

relevant features within the dataset, and export their

filtering results in different formats, including “.csv” and “.xlsx”,

among others.

In addition, to enhance user experience, we have implemented key

functionalities such as displaying formatted full protein

sequences, providing direct links to UniProt

entries, and enabling users to conveniently copy

complete sequences directly to their clipboard.

Altogether, the presented interface allows for efficient filtering and detailed examination of relevant data, ensuring a streamlined experience for researchers exploring LLPS-related data.

In this section, we present the guidelines to take full advantage of our web interface.

Table of Contents

Structure of the Web Interface

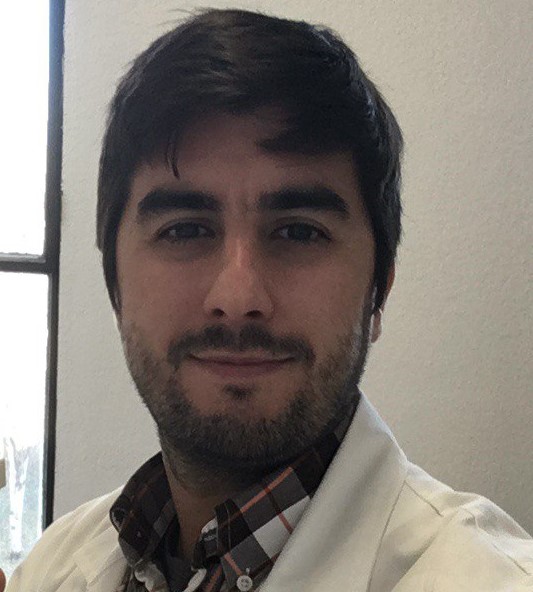

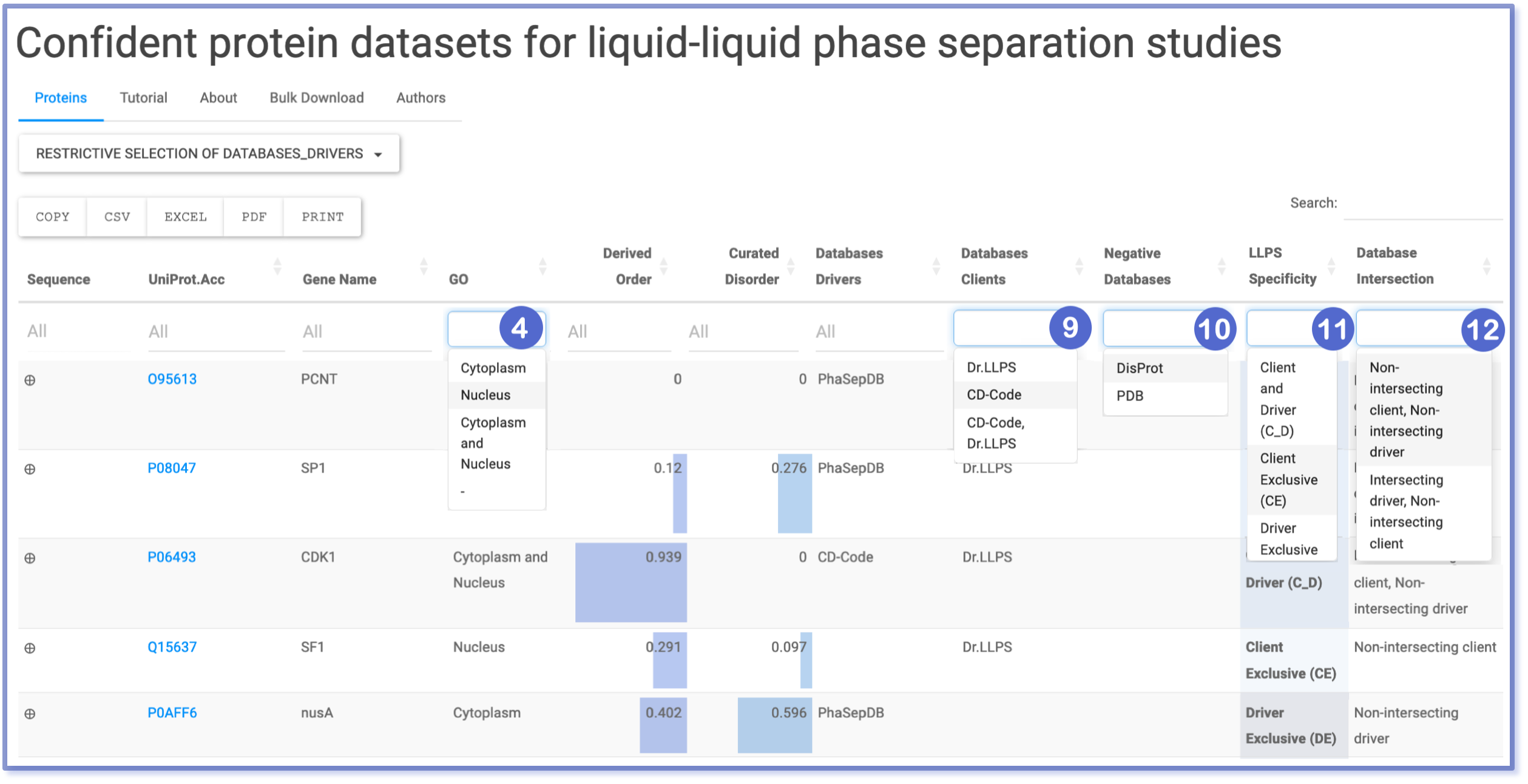

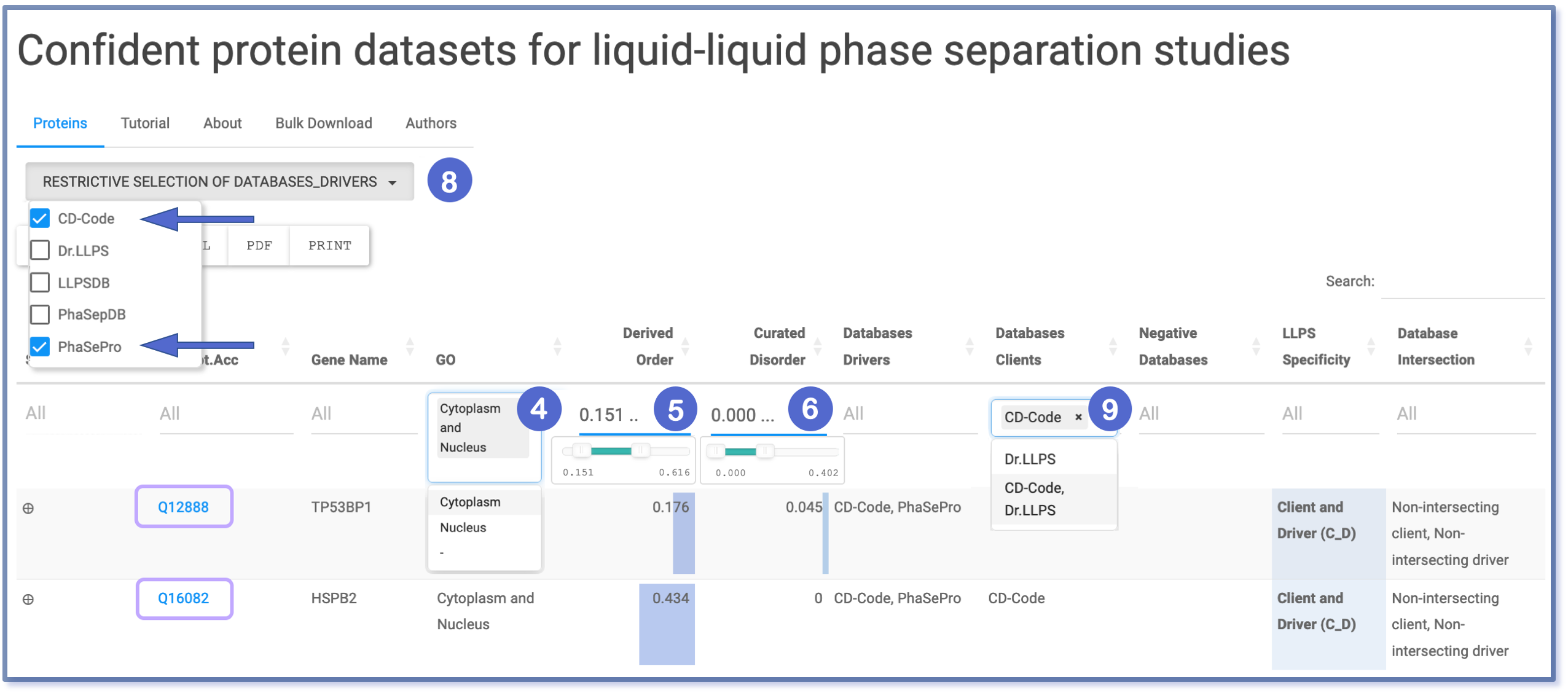

| Number | Content |

|---|---|

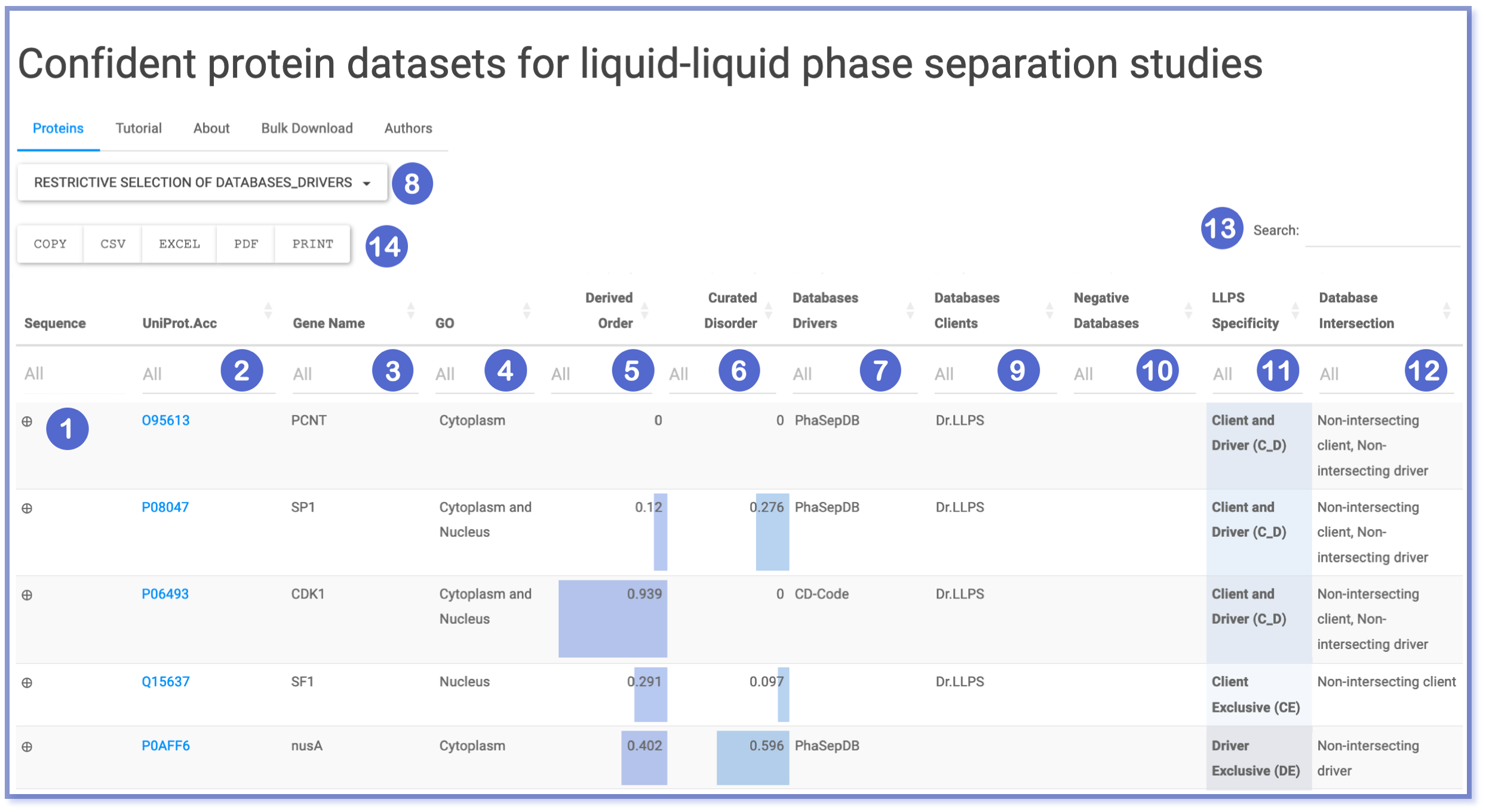

| (1) | Upon clicking the ‘plus’ sign ( ⊕ ), the full sequence of the protein is displayed in a text box, and the copy to clipboard sign ( 📋 ) appears, which allows to copy to clipboard the sequence without format. |

| (2) | This column provides direct link to UniProt entries. |

| (3) | This column entails the gene names of the proteins found in the dataset. |

| (4) | Gene Ontology annotations indicating cytoplasmic or nuclear localization, which can offer insights about selective compartmentalization. |

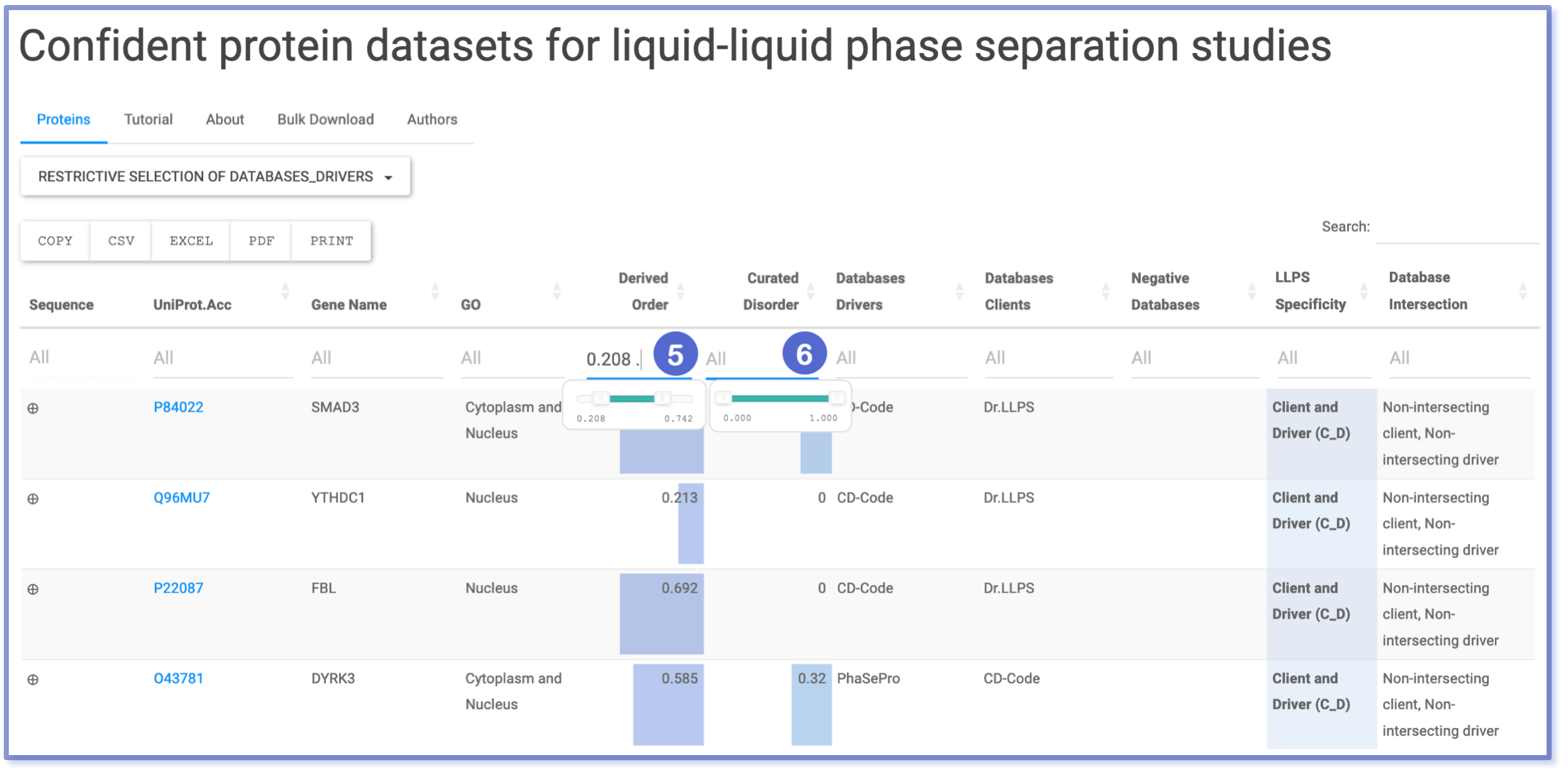

| (5) & (6) | The fraction of derived order and disorder, annotated by MobiDB, represented in little bar plots. |

| (7) & (9) & (10) | Information on protein’s source databases, categorized by drivers (➐), clients (➒), and negatives or non-LLPS participants (➓). |

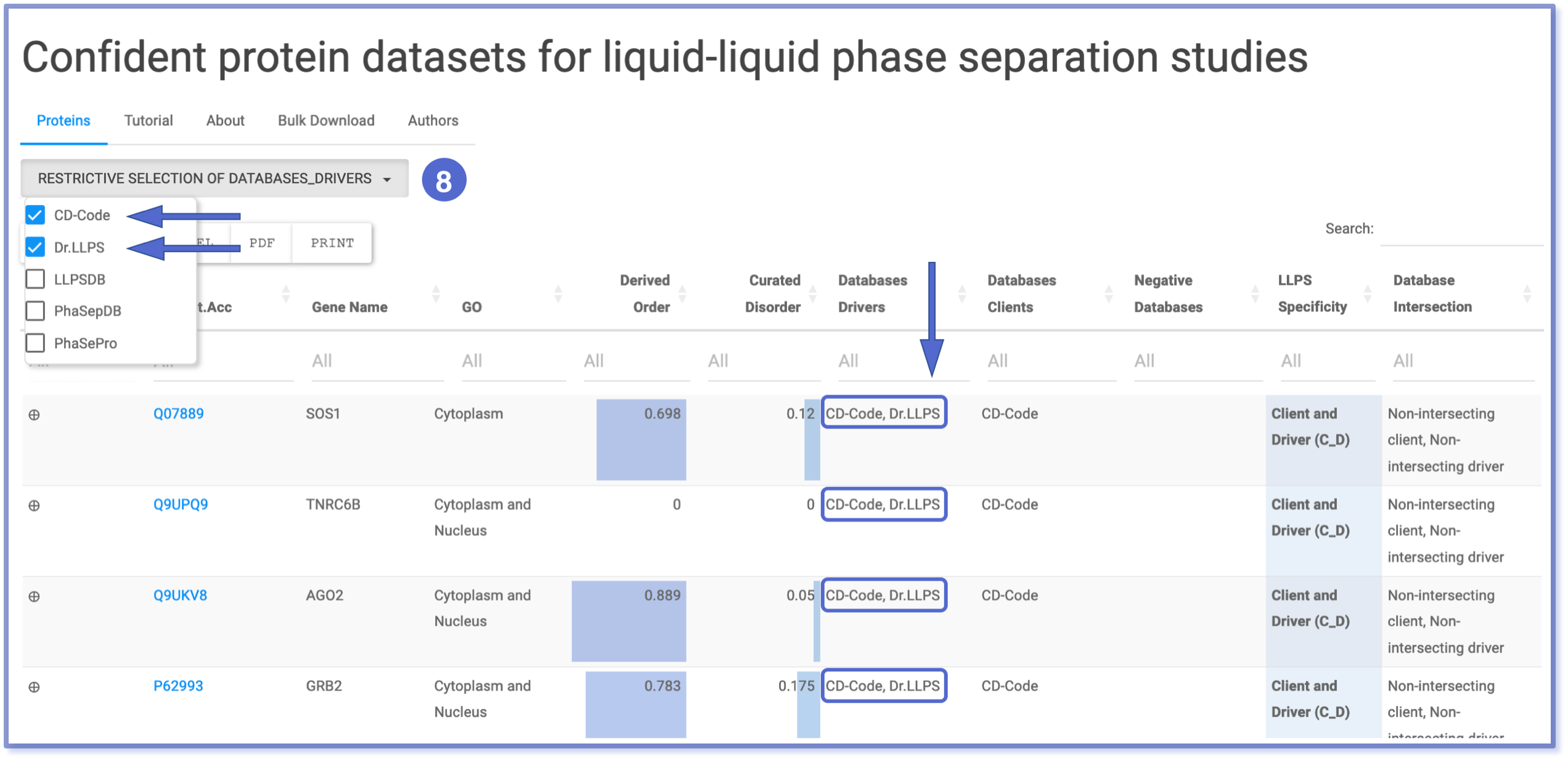

| (8) | Functional button allowing for restrictive filtering of drivers database (➐). It allows multiple selection. |

| (11) | LLPS specificity indicates classification as Client Exclusive (CE), Driver Exclusive (DE) or Client and Driver (C_D). |

| (12) | Database intersection analysis to estimate the number of occurrences in LLPS databases. |

| (13) | Generic ‘Search’ field. Typing search that filters in any of the provided columns. |

| (14) | Export options. |

Display Sequence and Copy To Clipboard

When the ‘plus’ sign (⊕) is clicked, users can access the protein’s complete sequence, presented in a responsive format. Subsequently, the ‘copy to clipboard’ icon (📋 , 1A) becomes available, allowing users to swiftly copy the sequence to the clipboard without any formatting included.

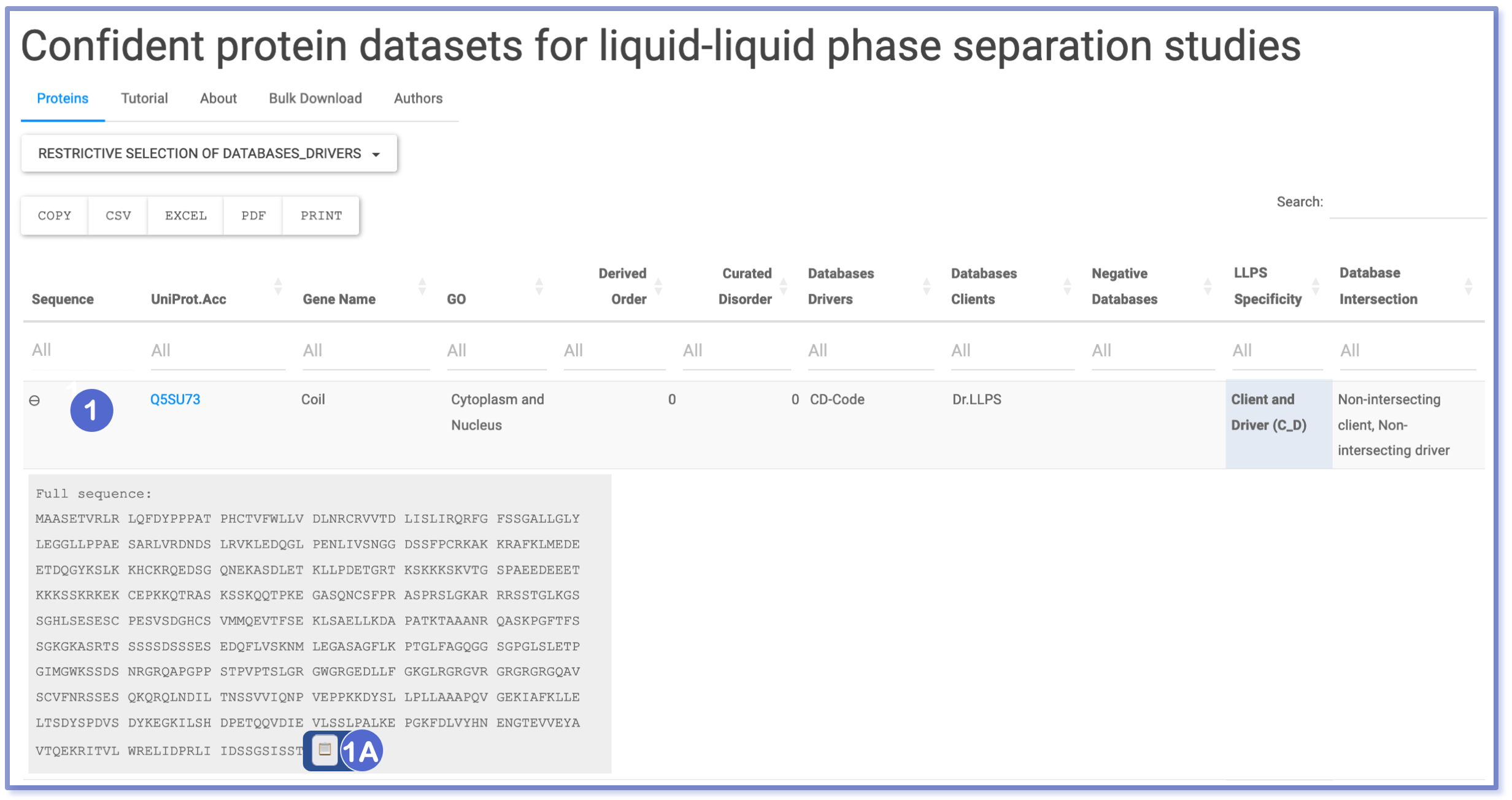

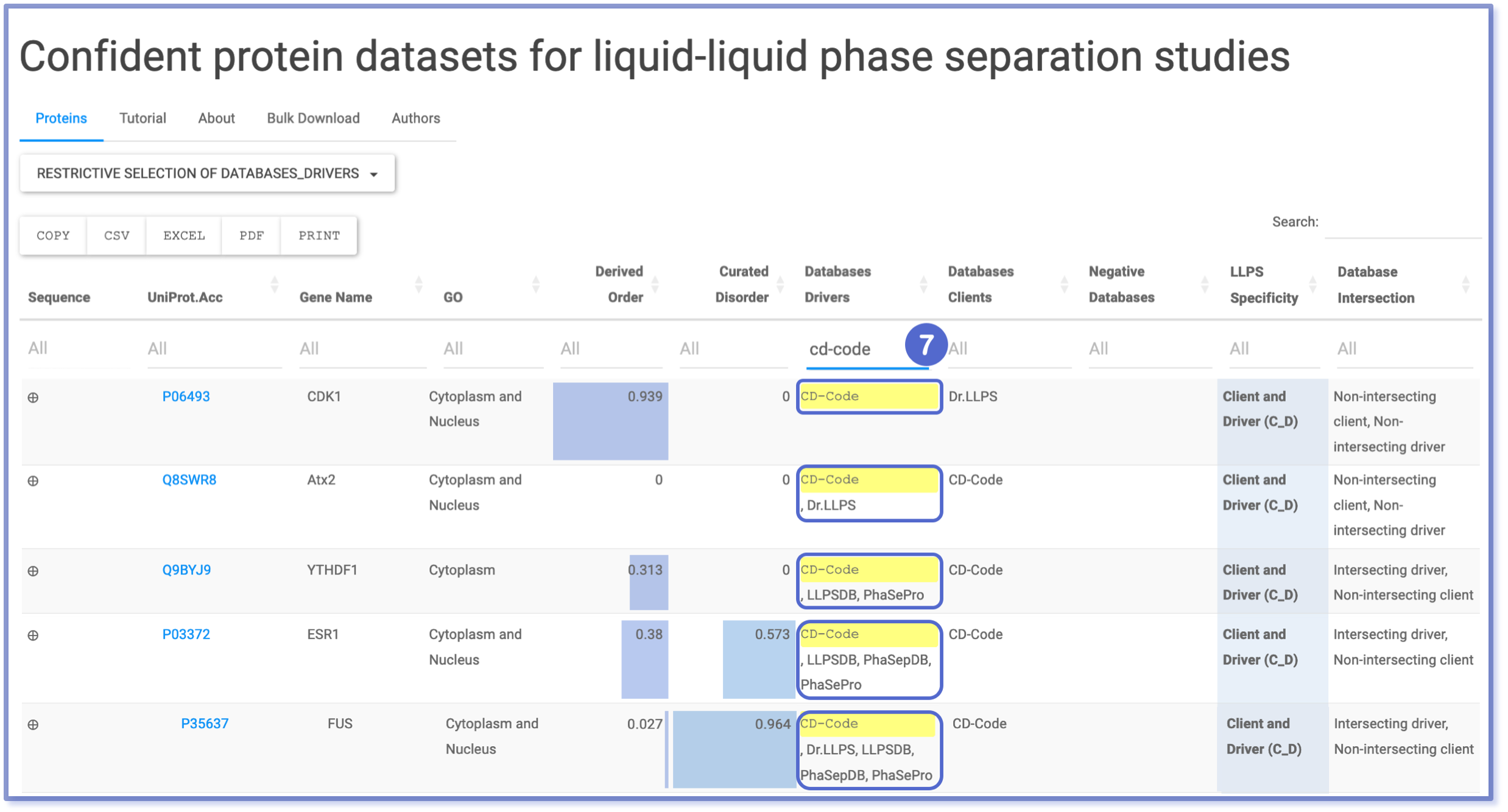

Filtering through Typing Search: UniProt, Gene Name and General Search

By employing the search feature within the UniProtID (number 2) and Gene Name (number 3) columns, users can refine their dataset queries by typing the input boxes, with the subsequent matched results highlighted in yellow for easy identification. Any entries not aligning with the query parameters are promptly filtered out, albeit without case sensitivity. Furthermore, the general top right “Search” box (number 13) extends search capabilities across the entire dataset. For instance, entering “client” will yield matches in both the “LLPS specificity” and “Database intersection” columns.

Filtering through Selection Menu: GO, Clients Database, Negative Database, LLPS specificity and Database intersection

The Selection Menu feature streamlines the filtering process by allowing users to choose specific options for filtering purposes. This intuitive method ensures precision by excluding entries that do not strictly match the query. Implemented in columns containing information on cellular localization (GO), databases (Databases Clients and Negative Databases), and classifications (LLPS specificity and Database intersection), this filtering mechanism enhances user experience and facilitates accurate data retrieval.

Filtering through Numeric Range: Fraction Order and Fraction Disorder

Columns containing numerical data are filtered using a range slider, allowing users to select the desired interval of values. This method is applied to the ‘Fraction Order’ (number 5) and ‘Fraction Disorder’ (number 6) columns, which are annotated by MobiDB. The figure demonstrates the use of conjunction filtering, where the displayed entries meet both filtering conditions simultaneously: the specified interval for ‘Fraction Order’ and the specified interval for ‘Fraction Disorder’.

Filtering through Typing Search & Restrictive Selection: Drivers Database

The ‘Databases Drivers’ column often contains entries linked to multiple databases, thus needing a versatile filtering approach. To accommodate this complexity, we have implemented two filtering methods. Firstly, the typing search filtering (number 7) allows users to retrieve entries based on their string-type query. This option will display all entries that match the search query, regardless of case sensitivity or exclusivity. For a more conservative filtering, users can use the ‘Restrictive Selection of Databases_Drivers’ button (number 8). This feature presents a checkbox dropdown menu, enabling users to filter for specific combinations of queries. However, it operates exclusively, meaning that only entries containing the exact query without additional options will be displayed.

Example of Conjunction Filtering

All the aforementioned filters operate using logical conjunction, meaning they produce a value of true only if all applied conditions are true. In practical terms, this translates to multiple filters working together as an ‘and’ operator. When combined, these filters refine the dataset by accumulating the filtering criteria, thereby enhancing the specificity and accuracy of the results.

About

This study presents confident datasets of client, driver and negative

proteins for LLPS analyses through an integrated biocuration protocol.

These datasets facilitate validation of physicochemical properties

relevant to LLPS, enable discrimination between LLPS participants and

set up the basis to establish fair benchmarks.

What is LLPS?

Eukaryotic cells harbor diverse intracellular substructures, among which

membrane-less bodies are formed through the intriguing phenomenon of

liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) [1]. While research has

traditionally focused on membrane-bound organelles like mitochondria,

there is a growing acknowledgment that LLPS plays a pivotal role in

governing diverse cellular processes including transcription, chromatin

organization, and DNA damage response (DDR), among others. Consequently,

LLPS has captivated attention in the last years for its physiological

relevance but also in disease, as its dysregulation has been linked to

neurodegenerative disorders such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)

or frontotemporal dementia (FTD) [2].

LLPS is a reversible biophysical process that occurs when a homogeneous mixture comprising multiple components spontaneously separates into two liquid phases, each with different concentrations of their constituents [3]. This phenomenon contributes to compartmentalization as it drives the formation of membrane-less organelles (MLOs), which serve to spatially confine and organize chemical reactions in the cell, acting as hubs of interactions [4]. Although these molecular condensates may involve a wide variety of proteins, only a small subset of these constituents are active LLPS participants, contributing to the condensate formation, structural integrity, and function. Thus, driver or scaffold proteins can undergo LLPS on their own, while client proteins are recruited to the pre-existing condensate [5].

Dataset contribution

As the number of identified phase separation proteins (PSPs) continues

to rise through experimental efforts, different computational methods

have emerged to develop LLPS sequence-based prediction tools.

Nevertheless, a key challenge in the development of these predictors

lies in the selection of an appropriate negative training

dataset, as the lack of a unified negative dataset hampers a

proper incorporation of this type of data into LLPS predictive models.

In some instances, predictors use the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) as

the negative set, which mainly comprises folded proteins, or the human

proteome, to encompass higher structural complexity. However, these

approaches can introduce an inherent bias in the prediction models by

potentially including many false positives that are intrinsically

disordered. That is, tools that exclusively rely on PDB for their

negative training dataset tend to differentiate between folded proteins

and intrinsically disordered regions or proteins (IDRs or IDPs) rather

than focusing on multivalent regions driving phase separation. This

limitation can hinder accurate PSP prediction, as many proteins can

undergo LLPS due to modular interaction domains [6].

Building on this perspective, the presence of order or

disorder in proteins does not always correspond with their

propensity for phase separation. Hence, it is crucial to consider

situations where disorder is observed in proteins that do not

phase-separate, or cases where folded proteins undergo LLPS

[7].

Furthermore, recent studies indicate that many existing predictors

struggle to identify non-phase-separating proteins, leading to

inadequate LLPS propensity prediction [8,9].

These limitations underscore the need for further refinement and

improvement in LLPS prediction tool development.

The datasets presented in this site offer a unique opportunity to

reassess the performance of current LLPS predictive methods and train

better models. The distinctive trait of these datasets is the

incorporation of well-defined negative sets,

specifically encompassing disordered proteins, along with a clear

distinction between client and driver proteins.

Additionally, the annotation of protein disorder

fraction within these datasets represents an excellent

opportunity to refine predictive tools, ensuring the avoidance of

sequential IDR biases [7]. Altogether, this framework should

lay a solid foundation for creating reliable benchmarks, opening the

door to a new generation of advanced LLPS predictive algorithms.

Information contained in the dataset

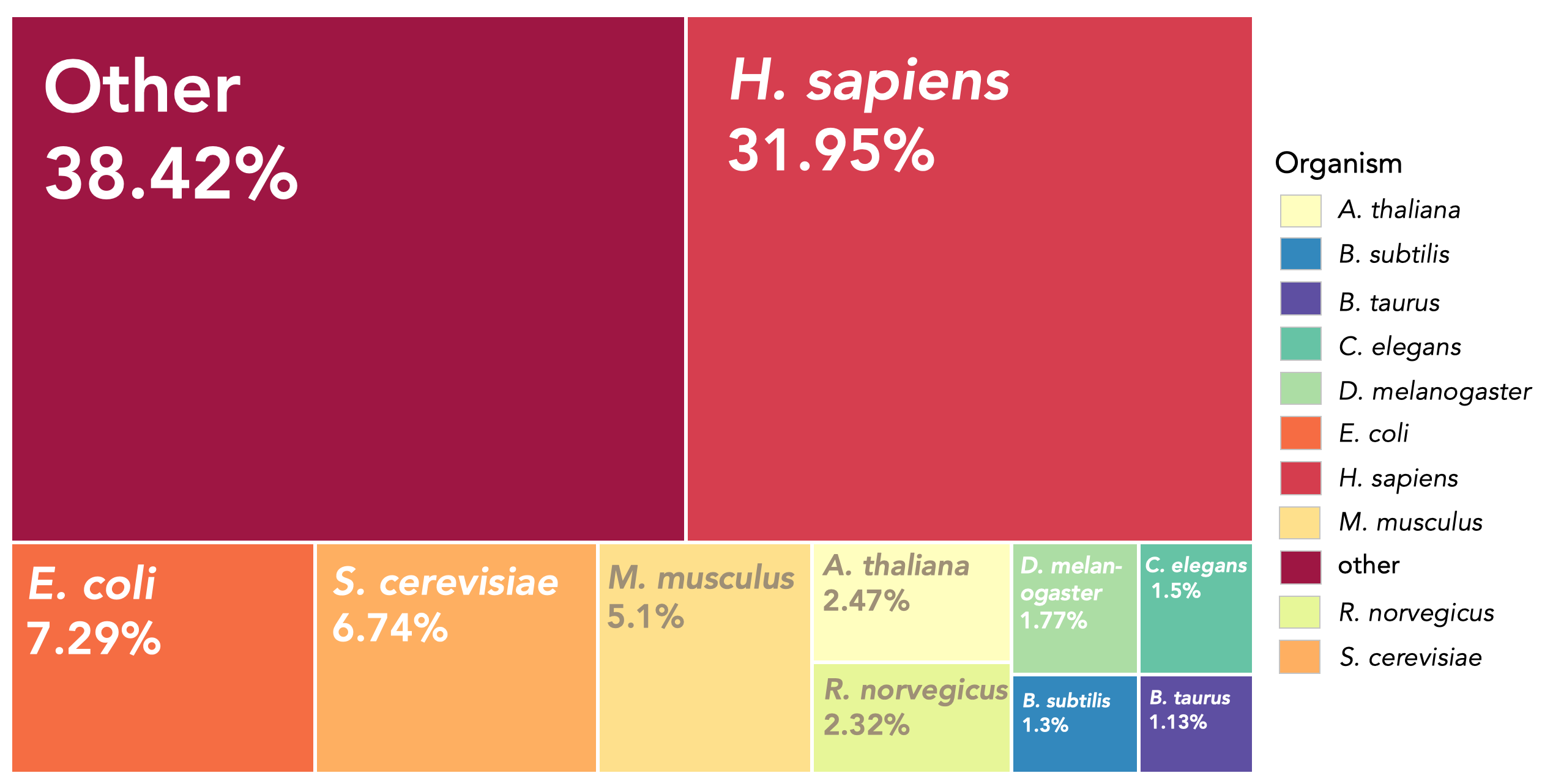

This dataset features over 600 client and driver proteins (positive

entries), along with more than 3,000 negative entries comprising both

disordered and ordered proteins. For each protein, the following

information can be accessed from the website:

- Direct link to UniProt entries.

- Full-length protein sequence upon clicking the “plus” sign.

- Database intersection analysis to identify the number of appearances of proteins in the original databases.

- Gene Ontology annotations indicating cytoplasmic or nuclear localization, which can offer insights into pathogenicity.

- The fraction of derived order and disorder, annotated by MobiDB.

- Information on the source databases of proteins, categorized by drivers, clients, and negatives.

- LLPS specificity indicated as Client Exclusive (CE), Driver Exclusive (DE) or Client and Driver (C_D).

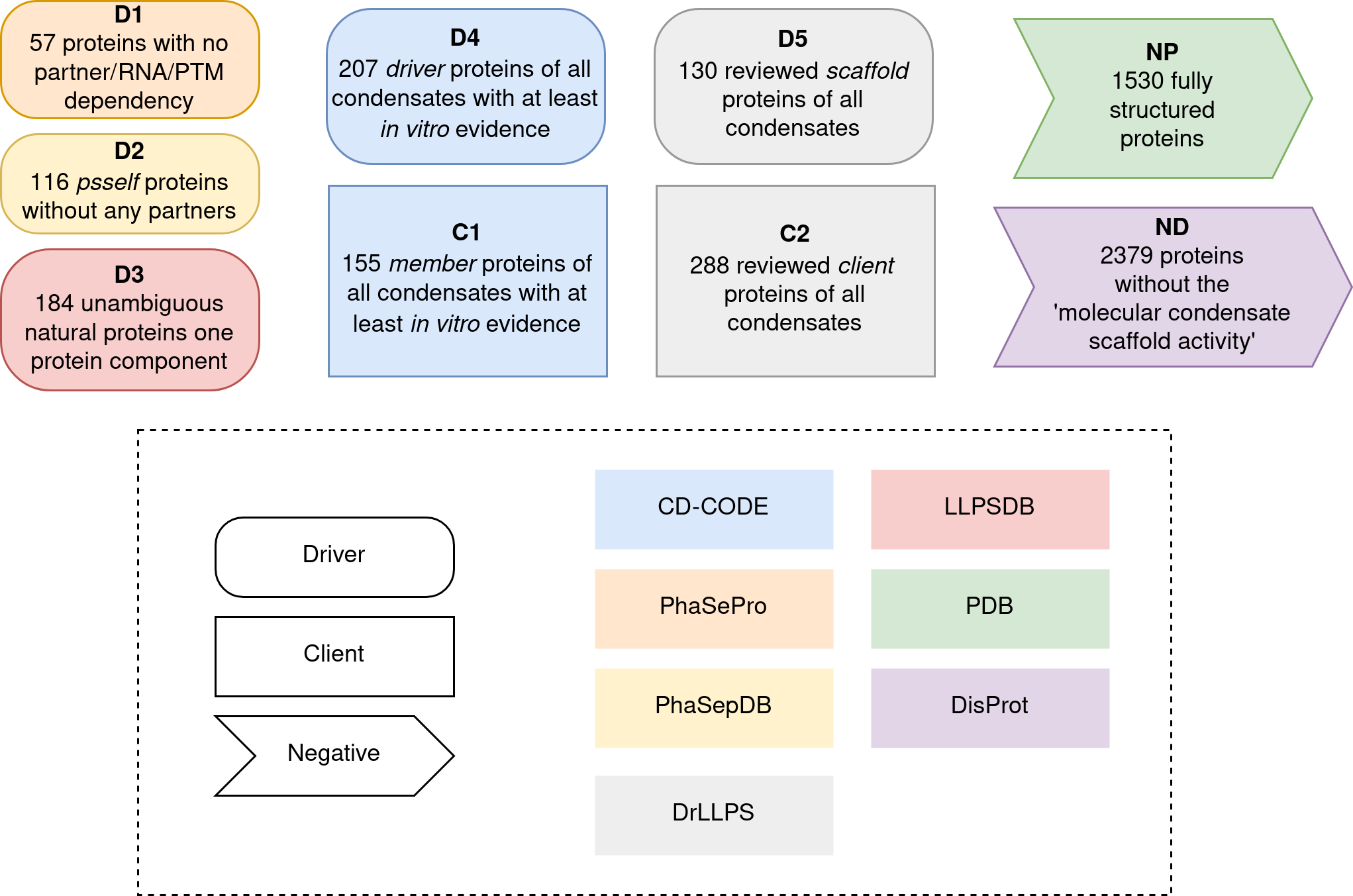

Construction of the dataset

Different filters were applied to original LLPS databases to obtain

similar levels of high-confidence drivers and clients. Besides, we

offered standardize negative datasets of both globular and disordered

proteins.

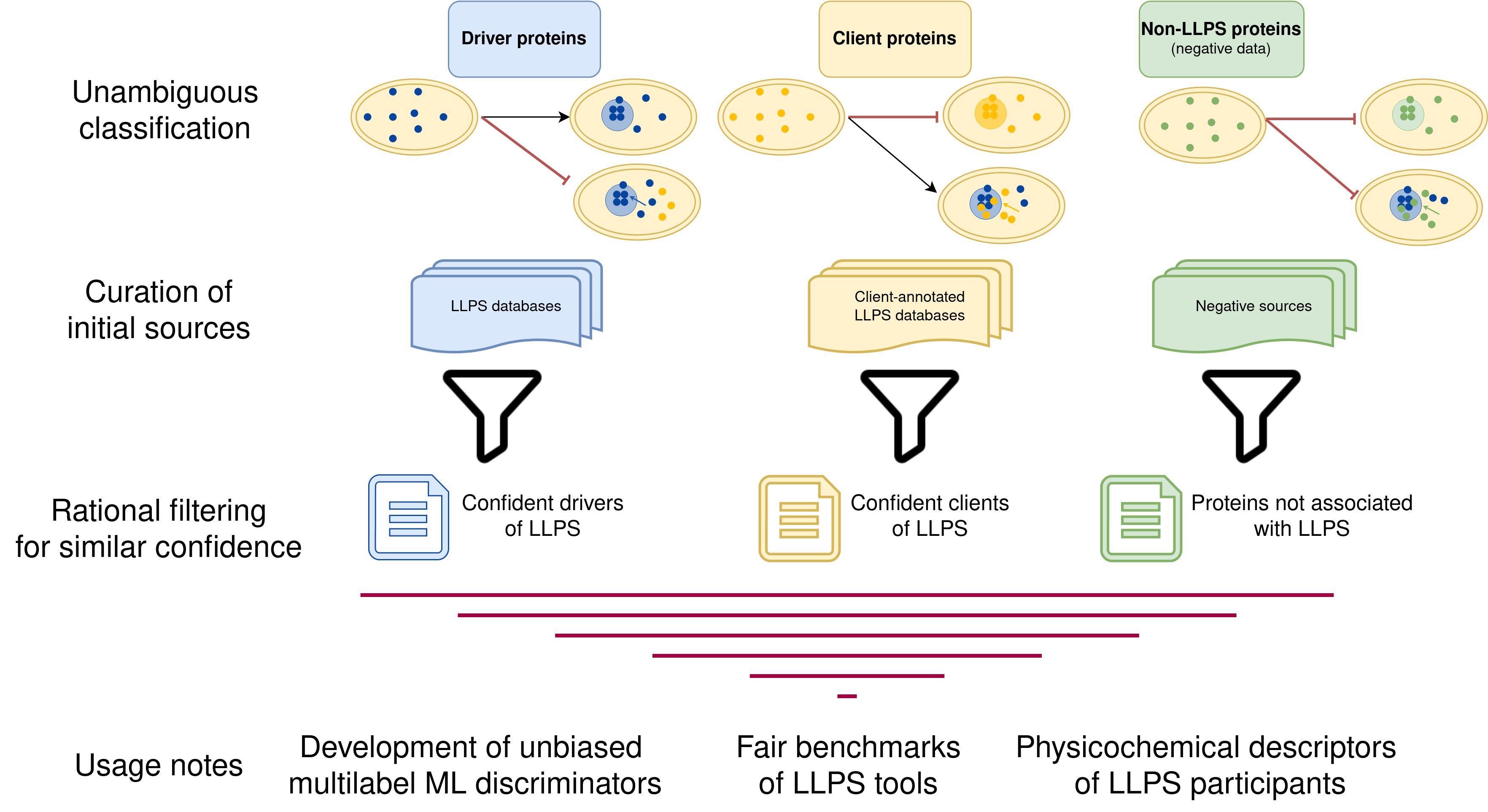

A schematic representation of the dataset generation is shown below. The

nature of each dataset (driver, client or negative) is described by the

shape of the box whereas the original source dataset can be identified

by its color. A description of the filters applied to each dataset is

briefly described inside each box.

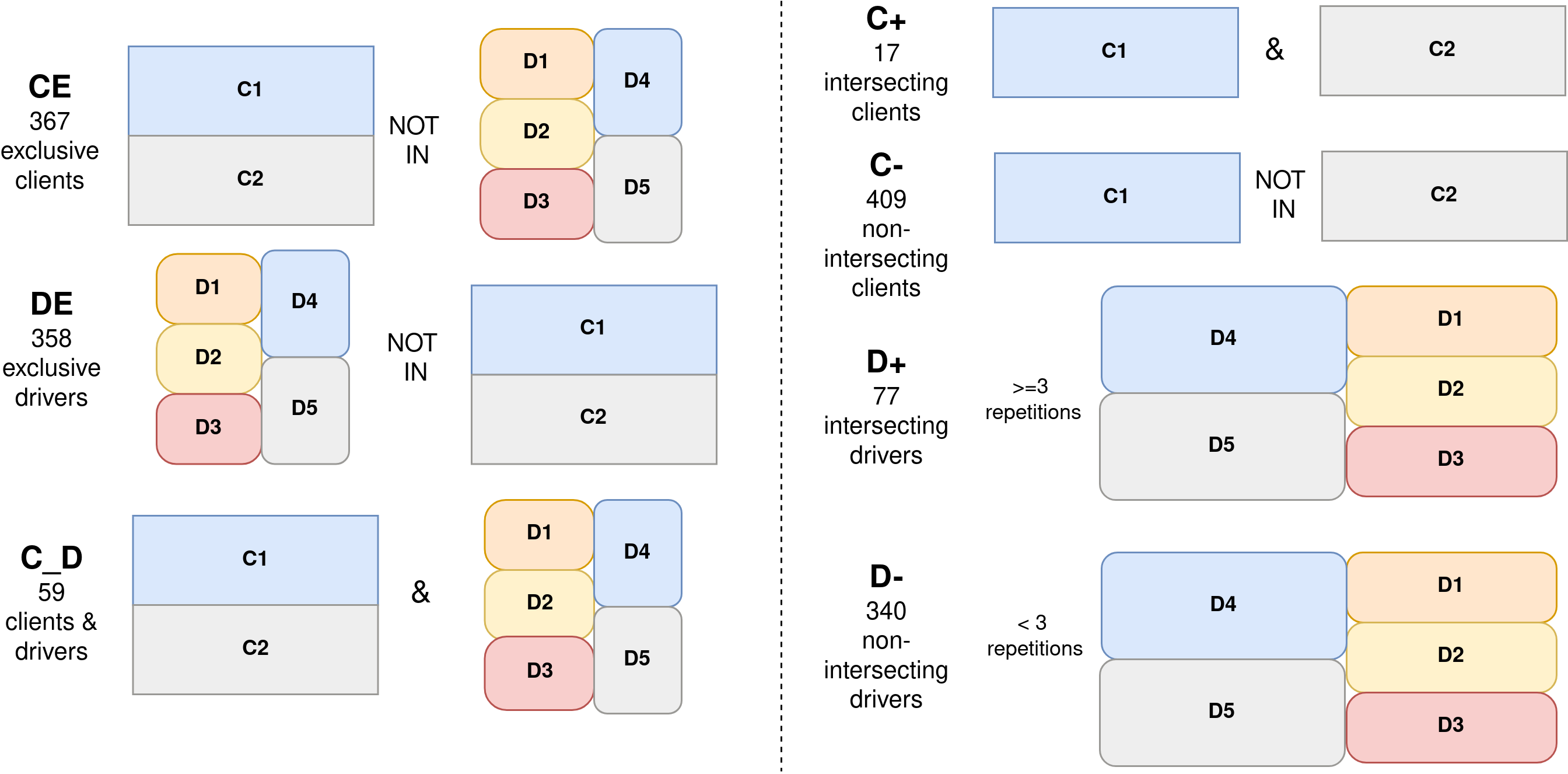

The identification of proteins with exclusive roles in condensates but also ambiguous entries can be useful to explain specific or context-dependent LLPS behaviors, respectively. For this purpose, we generated additional datasets for category specificity and database intersection, as shown below. On the left side, category specificity combinations are generated to obtain proteins that are exclusive clients (CE), exclusive drivers (DE), or both (C_D). On the right side, proteins are checked in all databases to ascertain intersecting clients (C+) and intersecting drivers (D+).

For a more detailed information about dataset generation, filtering methods, technical validation and subsequent applications, please check the corresponding manuscript (submitted).

References

[1] Wang, B., Zhang, L., Dai, T., Qin, Z., Lu, H., Zhang, L., & Zhou, F. (2021). Liquid– liquid phase separation in human health and diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 6 (1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-021-00678-1

[2] Portz, B., Lee, B. L., & Shorter, J. (2021). FUS and TDP-43 Phases in Health and Disease. Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 46(7), 550–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2020.12.005

[3] Xu, Z., Wang, W., Cao, Y., & Xue, B. (2023). Liquid-liquid phase separation: Fundamental physical principles, biological implications, and applications in supramolecular materials engineering. Supramolecular Materials, 2, 100049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.supmat. 2023.100049

[4] Hyman, A. A., Weber, C. A., & J ̈ulicher, F. (2014). Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation in Biology. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology, 30 (Volume 30, 2014), 39–58. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100913-013325

[5] Orti, F., Navarro, A. M., Rabinovich, A., Wodak, S. J., & Marino-Buslje, C. (2021). Insight into membraneless organelles and their associated proteins: Drivers, Clients and Regulators. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal, 19, 3964–3977. https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2021.06.042

[6] Cai, H., Vernon, R. M., & Forman-Kay, J. D. (2022). An Interpretable Machine-Learning Algorithm to Predict Disordered Protein Phase Separation Based on Biophysical Interactions. Biomolecules, 12 (8), 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12081131

[7] Hou, S., Hu, J., Yu, Z., Li, D., Liu, C., & Zhang, Y. (2024). Machine learning predictor PSPire screens for phase-separating proteins lacking intrinsically disordered regions. Nature Communications, 15 (1), 2147. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46445-y

[8] Shen, B., Chen, Z., Yu, C., Chen, T., Shi, M., & Li, T. (2021). Computational Screening of Phase-separating Proteins. Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics, 19 (1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gpb.2020.11.003

[9] Liao, S., Zhang, Y., Qi, Y., & Zhang, Z. (2023). Evaluation of sequence-based predictors for phase-separating protein. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 24 (4), bbad213. https://doi. org/10.1093/bib/bbad213

Bulk Download

| File | File format | Description |

|---|---|---|

| datasets.tsv | .tsv | Main dataset file with all proteins classified into driver, client, or negative. |

| sequential_elements.json | .json | JSON dictionary with IDRs and PrLDs for each protein. |

| GitHub repository | git | GitHub repository with main files and README. |